In 2016, the monetary policy framework moved towards flexible inflation targeting and a six member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was constituted for setting the policy rate. With this step towards modernization of the monetary policy process, India joined the set of countries that have adopted inflation targeting as their monetary policy framework. The Consumer Price Index (CPI combined) inflation target was set by the Government of India at 4% with ± 2% tolerance band for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021. In this backdrop, the paper reviews the evolution of monetary policy frameworks in India since the mid-1980s. It also describes the monetary policy transmission process and its limitations in terms of lags and rigidities. It highlights the importance of unconventional monetary policy measures in supplementing conventional tools especially during the easing cycle. Further, it examines the voting pattern of the MPC in India and compares this with that of various developed and emerging economies. The synchronization of cuts in the policy rate by MPCs of various countries during the global slowdown in 2019 and the COVID-19 pandemic in the early 2020s is also analysed.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The monetary policy framework in India has evolved over the past few decades in response to financial developments and changing macroeconomic conditions. The operational framework of monetary policy has also gone through significant changes with respect to instruments and targeting mechanisms. The preamble of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 was also amended in 2016, which now clearly provides the mandate of the RBI. It reads as follows:

“to regulate the issue of Bank notes and keeping of reserves with a view to securing monetary stability in India and generally to operate the currency and credit system of the country to its advantage; to have a modern monetary policy framework to meet the challenge of an increasingly complex economy; to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth.”

The aim of monetary policy in the initial years of inception of RBI was mainly to maintain the sterling parity, with exchange rate being the nominal anchor of monetary policy. Liquidity was regulated through open market operations (OMOs), bank rate and cash reserve ratio (CRR). Soon after independence and through the late 1960s, the role of the central bank was aligned with the planned development process of the nation in accordance with the 5-year plans. Thus, it played a major role in regulating credit availability, employing OMOs, bank rate, and reserve requirement towards this end.

With the nationalization of major banks in 1969, the main objective of monetary policy through the 1970s till the mid-1980s was the regulation of credit in accordance with the developmental needs of the country. This period was marked by monetization of fiscal deficit while inflationary consequences of high public expenditure necessitated frequent recourse to CRR.

In 1985, on the recommendation of the Committee set up to Review the Working of the Monetary System (Chairman: Dr. Sukhamoy Chakravarty), a new monetary policy framework, monetary targeting with feedback was implemented based on empirical evidence of a stable demand for money function. However, financial innovations in the 1990s implied that demand for money may be affected by factors other than income. Further, interest rates were deregulated in the mid-1990s and the Indian economy was getting increasingly integrated with the global economy. Therefore, the RBI began to deemphasize the role of monetary aggregates and implemented a multiple indicator approach (MIA) to monetary policy in 1998 encompassing all economic and financial variables that influence the major objectives outlined in the Preamble of the RBI Act. This was done in two phases—initially MIA and later augmented MIA (AMIA) which included forward looking variables and time series models.

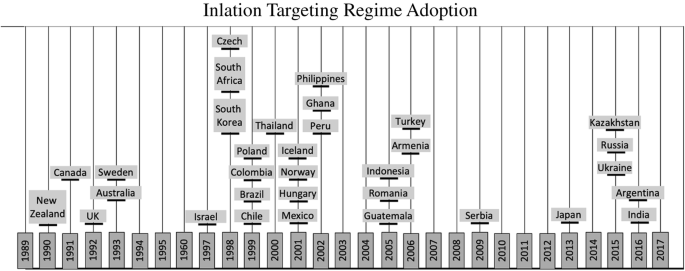

Based on RBI’s Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (2014, Chairman: Dr Urjit R Patel), a formal transition was made in 2016 towards flexible inflation targeting and a six member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was constituted for setting the policy repo rate. The Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA) was signed between the Government of India and the RBI in February 2015 to formally adopt the flexible inflation targeting (FIT) framework. This was followed up with the amendment to the RBI Act, 1934 in May 2016 to provide a statutory basis for the implementation of the FIT framework. With this step towards modernization of the monetary policy process, India joined the set of countries that adopted inflation targeting, starting from 1990 by New Zealand, as their monetary policy framework. The Central Government notified in the Official Gazette dated August 5, 2016, that the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation target would be 4% with ± 2% tolerance band for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021. At the time of writing (April 2020), this period is drawing to a close in less than a year. In this backdrop, this paper discusses the evolution of the monetary policy framework in India and describes the workings of the current framework.

The paper is divided into the following sections. Section 2 presents a schematic representation of the main components of a general monetary policy framework and describes its key features. Section 3 describes the genesis of the monetary policy framework in India since 1985 covering the Monetary Targeting Framework, Multiple Indicator Approach and Flexible Inflation Targeting. The main recommendations of RBI’s Report of the Expert Committee to Revise and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (2014, Chairman: Dr Urjit R Patel) are also discussed. Composition, workings and voting pattern of the Monetary Policy Committee from October 2016 to March 2020 are also provided. Further, a comparison of voting patterns with various countries across the globe is undertaken.

Section 4 discusses a general framework for monetary policy transmission and applies the framework to India. It also describes interest rate linkages at the global level. Section 5 examines unconventional monetary policy measures adopted in late 2019 and early 2020. Section 6 concludes the paper.

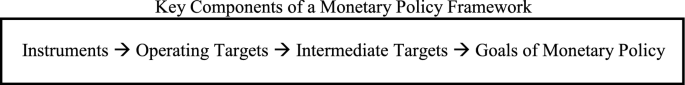

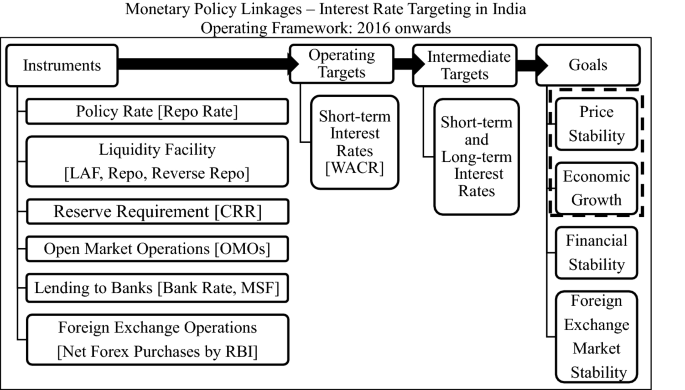

The specification of the monetary policy framework facilitates the conduct of monetary policy. The general framework comprises well-defined objectives/goals of monetary policy along with instruments, operating targets and intermediate targets that aid in the implementation of monetary policy and achievement of the ultimate objectives. A schematic representation of a monetary policy framework is shown in Fig. 1 (Laurens et al. 2015; Mishkin 2016).

Instruments are tools that the central bank has control over and are used to achieve the operational target. Examples of instruments include open market operations, reserve requirements, discount policy, lending to banks, policy rate. Operational targets are the financial variables that can be controlled by the central bank to a large extent through the monetary policy instruments and guide the day-to-day operations of the central bank. These can impact the intermediate target and thus help in the delivery of the final goal of monetary policy. Examples of operational targets include reserve money and short-term money market interest rates.

Intermediate targets are variables that are closely related with the final goals of monetary policy and can be affected by monetary policy. Intermediate targets may include monetary aggregates and short-term and long-term interest rates. Goals refer to the final policy objectives. These may include price stability, economic growth, financial stability and exchange rate stability.

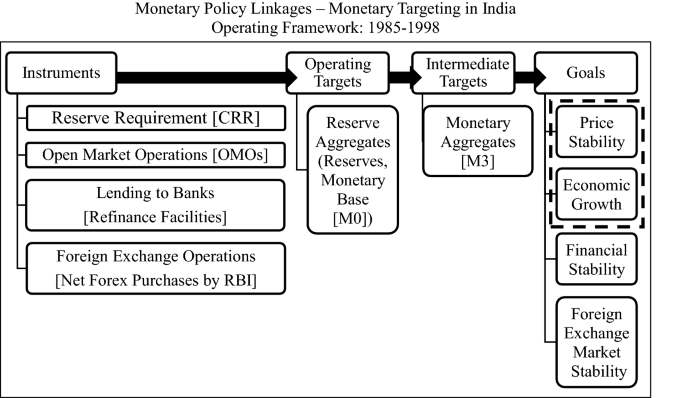

This general framework is applied to the monetary targeting framework with feedback that prevailed from 1985 to 1998 and to the inflation targeting framework that exists from 2016 onwards. The multiple indicator approach that was operational from 1998 to 2016 was based on a number of financial and economic variables and was not exactly specified on the basis of this framework although broad money was treated as an intermediate target and the goals of monetary policy are the same across the various frameworks.

In the 1970s through the mid-1980s, monetization of the fiscal deficit exerted a dominant influence on monetary policy with inflationary consequences of high public expenditure necessitating frequent recourse to CRR. Against this backdrop, in 1985, on the recommendation of the Committee set up to Review the Working of the Monetary System (RBI 1985; Chairman: Dr. Sukhamoy Chakravarty), a new monetary policy framework, monetary targeting with feedback was implemented based on empirical evidence of a stable demand for money function. The recommendation of the committee was to control inflation within acceptable levels with desired output growth. Further, instead of following a fixed target for money supply growth, a range was followed which was subject to mid-year adjustments. This framework was termed “Monetary Targeting with Feedback” as it was flexible enough to accommodate changes in output growth.

This operational framework is depicted in Fig. 2. (Definitions of variables shown in Fig. 2 are given in Appendix 1). The main instruments in this framework were cash reserve ratio (CRR), open market operations (OMOs), refinance facilities and foreign exchange operations. Broad money (M3) was chosen as the intermediate target while reserve money (M0) was the main operating target. However, an analysis of money growth outcomes during the monetary targeting framework reveals that targets were rarely met (RBI 2009–2012). Even with increases in CRR, money supply growth remained high and fuelled inflation.

Further, financial innovations in the 1990s implied that demand for money may be affected by factors other than income. Since the mid-1990s, with global integration, factors such as swings in capital flows, volatility in the exchange rate and global growth also impacted the economy. Moreover, interest rates were deregulated allowing for changing interest rates and a market determined management system of exchange rates was also adopted.

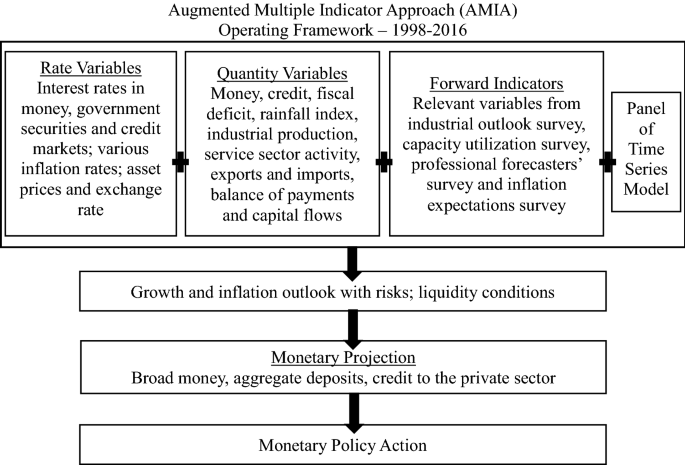

Against the backdrop of changing domestic and global dynamics, RBI implemented a multiple indicator approach (MIA) to monetary policy in 1998 encompassing various economic and financial variables based on the recommendations of RBI’s Working Group on Money Supply (RBI 1998; Chairman: Dr YV Reddy). These variables included several quantity variables such as money, credit, output, trade, capital flows, fiscal indicators as well as rate variables such as interest rates, inflation rate and the exchange rate. The information on these variables provided a broad-based monetary policy formulation, which not only encompassed a diverse set of information, but also accorded flexibility to the conduct of monetary management. The MIA was conceptualized when Dr Bimal Jalan was Governor and was implemented in two stages—MIA and later augmented MIA, by including forward looking variables and a panel of time series models, in addition to the economic and financial variables (Mohanty 2010; Reddy 1999). Forward looking indicators were drawn from RBI’s industrial outlook survey, capacity utilization survey, inflation expectations survey and professional forecasters’ survey. All the variables together with time series models provided the projection of growth and inflation while RBI provided the projection for broad money (M3) and treated this as the intermediate target.

The operational framework of AMIA is illustrated in Fig. 3. Compared to the Monetary Targeting Framework, the goals of monetary policy remained the same and broad money continued to serve as the intermediate target while the underlying operating mechanism of MIA evolved over time. In May 2011, the weighted average call money rate (WACR) was explicitly recognized as the operating target of monetary policy while the repo rate was made the only one independently varying policy rate. These measures improved the implementation and transmission of monetary policy along with enhancing the accuracy of signaling of monetary policy stance (Mohanty 2011).

Shift towards inflation targeting

The importance of focusing on inflation was first highlighted in the Report of the Committee on Financial Sector Reforms (Government of India 2009; Chairman: Dr. Raghuram Rajan) constituted by the Government of India. The report recommended that RBI can best serve the cause of growth by focusing on controlling inflation and intervening in currency markets only to limit excessive volatility. The report pointed out that the cause of inclusion can also be best served by maintaining this focus because the poorer sections are least hedged against inflation. Further, the report recommended that there should be a single objective of staying close to a low inflation number, or within a range, in the medium term, moving steadily to a single instrument, the short-term interest rate to achieve it.

Former RBI Governor, Dr. Raghuram Rajan set up an Expert Committee in 2013 to Review and Strengthen the Monetary Policy Framework (RBI 2014; Chairman: Dr Urjit R Patel). The mandate of the Committee, amongst others, was to review the objectives and conduct of monetary policy in a globalized and highly inter-connected environment. The committee was also required to review the organizational structure, operating framework and instruments of monetary policy, liquidity management framework, to ensure compatibility with macroeconomic and financial stability, as well as market development. The impediments to monetary policy transmission were to be identified and measures along with institutional pre-conditions to improve transmission across financial markets and real economy were to be suggested.

Some issues central to the report were selecting the nominal anchor for monetary policy, defining the inflation metric and specifying the inflation target. A nominal anchor is central to a credible monetary policy framework as it ties down the price level or the change in the price level to attain the final goal of monetary policy. It is a numerical objective that is defined for a nominal variable to signal the commitment of monetary policy towards price stability.

Generally five types of nominal anchors have been used, namely, monetary aggregates, exchange rate, inflation rate, national income and price level. The Expert Committee recommended inflation to be the nominal anchor of the monetary policy framework in India as flexible inflation targeting recognizes the existence of growth-inflation trade-off in the short-run and stabilizing and anchoring inflation expectations is critical for ensuring price stability on an enduring basis. Further, low and stable inflation is a necessary precondition for sustainable high growth and inflation is also easily understood by the public.

Regarding the inflation metric, the Committee recommended that RBI should adopt the all India CPI (combined) inflation as the measure of the nominal anchor. This is to be defined in terms of headline CPI inflation, which closely reflects the cost of living and influences inflation expectations relative to other available metrics. CPI is also easily understood as it is used as a reference in wage contracts and negotiations. Headline inflation was preferred against core inflation (headline inflation excluding food and fuel inflation) since food and fuel comprise more than 50% of the consumption basket and cannot be discarded.

The Committee recommended the target level of inflation at 4% with a band of ± 2% around it. The tolerance band was formulated in the light of the vulnerability of the Indian economy to supply and external shocks and the relatively large weight of food in the CPI basket.

The Expert Committee also recommended that decision-making should be vested in a Monetary Policy Committee (MPC).

With the signing of the Monetary Policy Framework Agreement (MPFA) between the Government of India and the RBI on Feb 20, 2015, Flexible Inflation Targeting (FIT) was formally adopted in India. In May 2016, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) Act, 1934 was amended to provide a statutory basis for the implementation of the FIT framework. The amended RBI Act, 1934 also provided that the Central Government shall, in consultation with the Bank, determine the inflation target in terms of the Consumer Price Index, once in every 5 years.

Accordingly, the Central Government has notified in the Official Gazette 4% Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation as the target for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021 with the upper tolerance limit of 6% and the lower tolerance limit of 2%. The amended RBI Act, 1934 also provides that RBI shall be seen to have failed to meet the target if inflation remains above 6% or below 2% for three consecutive quarters. In such circumstances, RBI is required to provide the reasons for the failure, and propose remedial measures and the expected time to return inflation to the target.

In 2016, India thus joined several developed and emerging market economies that have implemented inflation targeting. Figure 4 shows the timeline for implementation of inflation targeting for countries in this category, starting in 1990.

Monetary Policy Committee: composition, monetary policy framework and voting patterns

The amended RBI Act, 1934 provides for a statutory and institutionalized framework for a six-member Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) to be constituted by the Central Government by notification in the Official Gazette. The Central Government in September 2016 thus constituted the MPC with three members from RBI including the Governor as Chairperson and three external members as per Gazette Notification dated September 29, 2016. (Details of the composition of MPC are given in Appendix 3). The Committee is required to meet at least four times a year although it has been meeting on a bi-monthly basis since October 2016. Each member of the MPC has one vote, and in the event of equality of votes, the Governor has a second or casting vote. The resolution adopted by the MPC is published after conclusion of every meeting of the MPC. On the 14th day, the minutes of the proceedings of the MPC are published which includes the resolution adopted by the MPC, the vote of each member on the resolution, and the statement of each member on the resolution.

It may be noted that before the constitution of the MPC, a Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) on Monetary Policy was set up in 2005 which consisted of external experts from monetary economics, central banking, financial markets and public finance. The role of this committee was to enhance the consultative process of monetary policy by reviewing the macroeconomic and monetary developments in the economy and advising RBI on the stance of monetary policy. With the formation of MPC, the TAC on Monetary Policy ceased to exist.

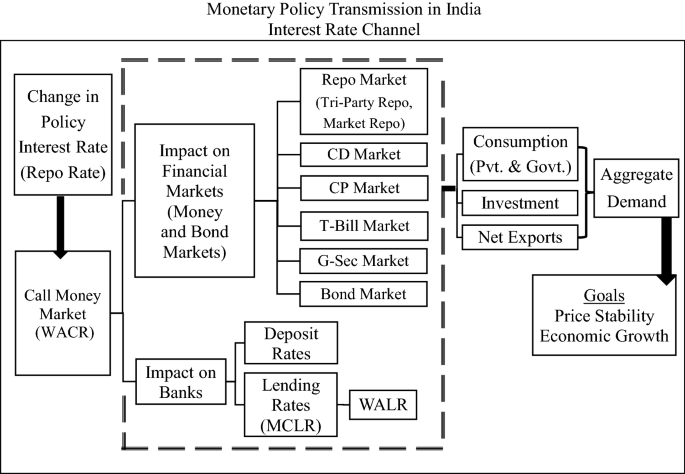

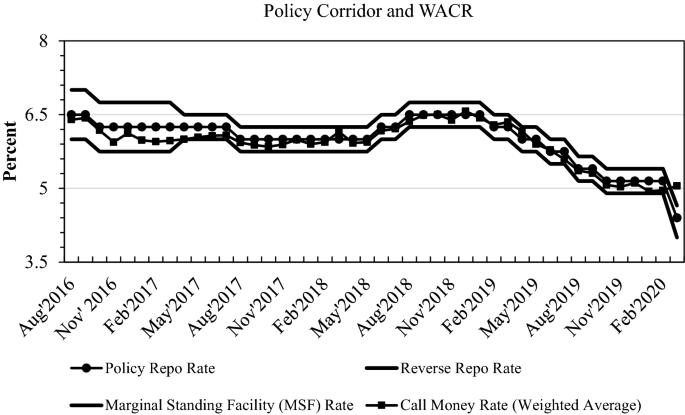

The MPC is entrusted with the task of fixing the benchmark policy rate (repo rate) required to contain inflation within the specified tolerance band. The framework entails setting the policy rate on the basis of current and evolving macroeconomic conditions. Once the repo rate is announced, the operating framework looks at liquidity management on a day-to-day basis with the aim to anchor the operating target—the weighted average call rate (WACR)—around the repo rate. This is illustrated in Fig. 5, where the intermediate targets are the short-term and long-term interest rates and the goals of price stability and economic growth are aligned with the primary objective of monetary policy to maintain price stability, keeping in mind the objective of growth. In addition to the repo rate, the instruments include liquidity facility, CRR, OMOs, lending to banks and foreign exchange operations (RBI 2018).

It is imperative here to note some of the key elements of the revised framework for liquidity management (RBI 2019) that are particularly relevant for the operating framework shown in Fig. 5. As noted in the RBI Monetary Policy Report, 2020.

The first meeting of the MPC was held in October 2016. Between October 2016 and March 2020, the MPC has met 22 times. Table 1 shows the voting patterns for each meeting with respect to the direction of change in the policy rate, magnitude of change and the stance of monetary policy. Table 2, on the other hand, provides an overall summary of the voting of all the meetings. It is interesting to note in Table 2, that with respect to direction of change/status quo of the policy rate, consensus was achieved in 12 meetings out of 22. Of these 12 meetings, there were three meetings where there were differences in the magnitude of the change voted for although there was consensus regarding the direction of change. The diversity in voting of the MPC members reflects the differences in the assessment and expectations of individual members as well as their policy preferences.

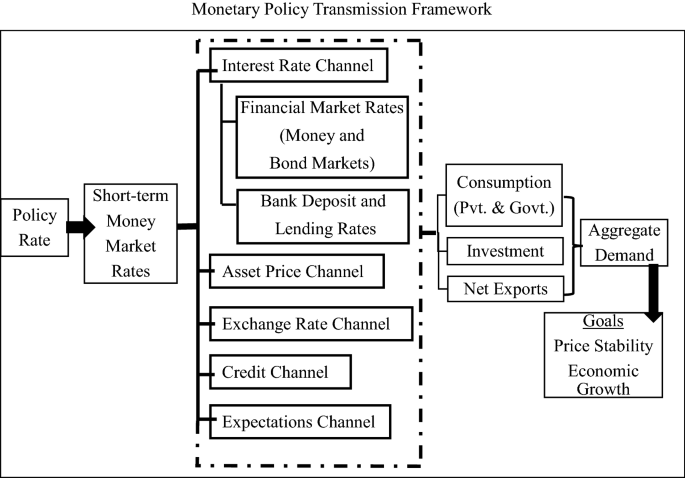

The transmission mechanism is beset with lags. As explained in simple terms in Rangarajan (2020), there are two components of the transmission mechanism. The first is how far the signals sent out by the central bank are picked by the banks and the second is how far the signals sent out by the banking system impact the real economy. Rangarajan (2020) labels the first component as “inner leg” and the second as “outer leg”.

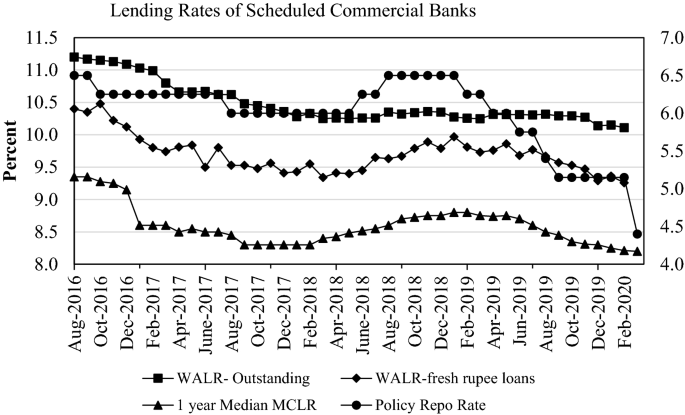

To illustrate monetary transmission of the first kind, we examine the impact of a cumulative reduction in the policy repo rate by 135 basis points between February 2019 and January 2020. During this period, transmission to various money and bond markets ranged from 146 basis points in the overnight call money market to 73 basis points in the market for 5-year government securities to 76 basis points in the market for 10-year government securities. Transmission to the credit market was also modest with the 1-year median marginal cost of funds-based lending rate (MCLR) declining by 55 basis points during February 2019 and January 2020. The weighted average lending rate (WALR) on fresh rupee loans sanctioned by banks fell by 69 basis points while the WALR on outstanding rupee loans declined by 13 basis points during February to December 2019.

Monetary transmission increased somewhat after the introduction of the external benchmark system in October 2019 whereby most banks have linked their lending rates to the policy repo rate of the Reserve Bank. During October to December 2019, the WALRs of domestic banks on fresh rupee loans fell by 18 basis points for housing loans, 87 basis points for vehicle loans and 23 basis points for loans to micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

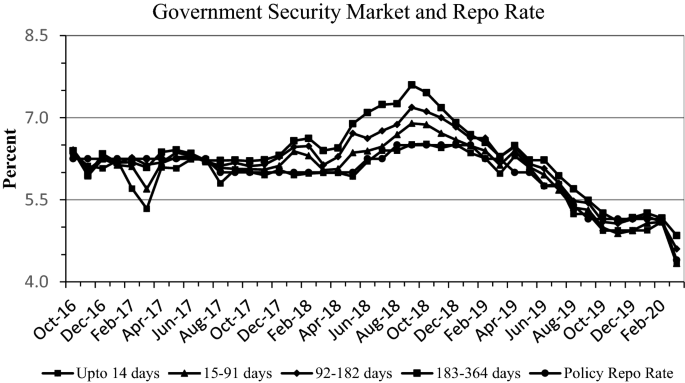

Monetary transmission in various markets is depicted in Figs. 8, 9 and 10. Figure 8 shows the policy corridor with the MSF rate as the ceiling and the reverse repo rate as the floor for the daily movement in the weighted average call money rate. The figure shows that the WACR moved closely in tandem with the policy rate (repo rate). Figure 9 shows that the G-Sec market rates followed the movements in the policy rate. Figure 10 shows that the direction of change of MCLR was more or less in synchronization with that of the repo rate. The WALR for fresh rupee loans tracked the repo rate much more than the WALR on outstanding loans.

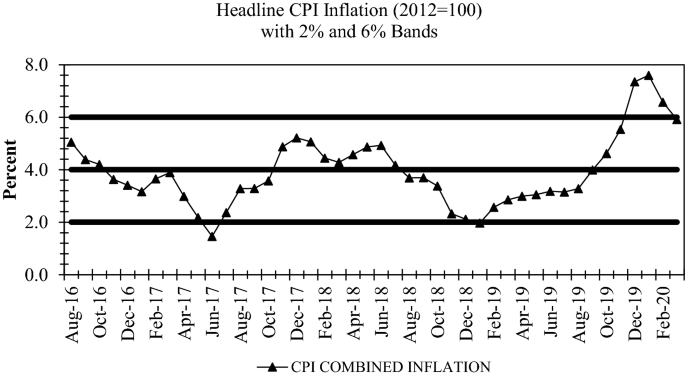

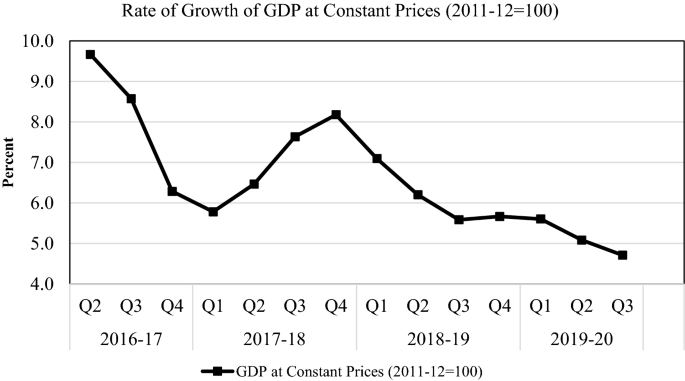

Figure 11 shows the 4% target inflation rate with the ± 2% tolerance band along with the headline inflation rate. This shows that the headline inflation generally stayed within the band. The average inflation rate from August 2016 to March 2020 was 3.93% and up to December 2019, it was 3.72%, i.e. close to 4%. The average GDP growth between Q2: 2016–2017 and Q3: 2019–2020 was 6.6% (Fig. 12).

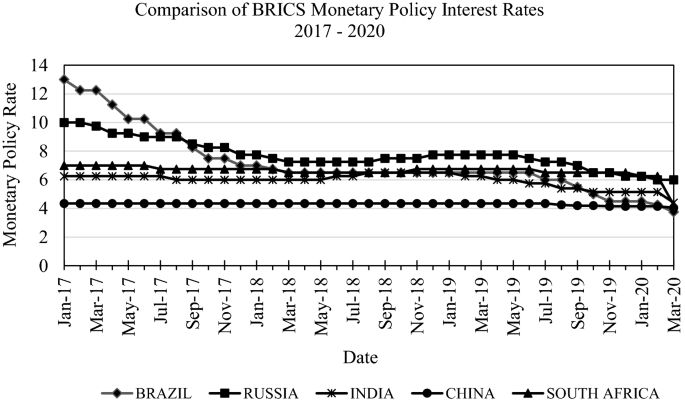

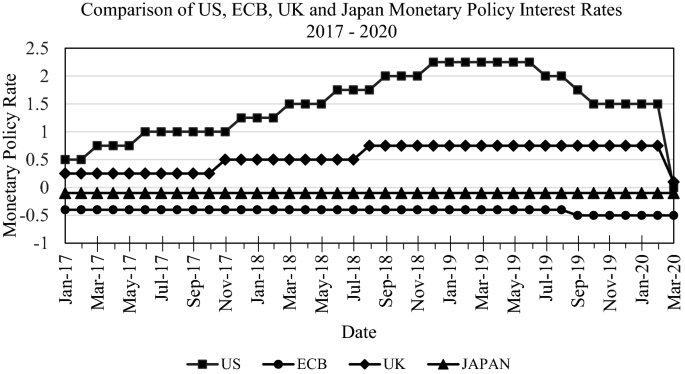

An interesting phenomena, world-wide is the synchronization in the movements in interest rates across the globe. Table 4 shows that MPCs in various countries have voted for a cut in their policy rate in 2019 at a time when many countries were simultaneously experiencing a slowdown. Due to COVID-19 pandemic, in early 2020, some countries have cut the policy rate sharply. This pattern of rate cuts in 2019 up to March 2020 is almost perfectly aligned with the movements in the repo rate (policy rate) in India. These global patterns are illustrated in Figs. 13 and 14. Figure 13 shows that the policy rates for the BRICS nations moved in tandem from 2017 to 2020. Figure 14 indicates a similar pattern amongst policy rates of US, ECB, UK and Japan.

We have so far discussed conventional monetary policy. As already described, monetary transmission of conventional monetary policy entails a change in the policy rate impacting financial markets from short-term interest rates to longer-term bonds and bank funding and lending rates. A change in the policy rate is thus expected to permeate through the entire spectrum of rates that further translates into affecting interest sensitive spending and thus economic activity. However, if there are problems in the monetary policy transmission mechanism or if additional monetary stimulus is required in the circumstances that the policy rate cannot be reduced further (or in addition to a change in the policy rate), then the central banks may employ unconventional monetary policy tools. Unconventional monetary measures target financial variables other than the short-term interest rate such as term spreads (e.g., interest rates on risk free bonds), liquidity, credit spreads (e.g. interest rates on risky assets) and asset prices. The objective of unconventional tools is to supplement the conventional monetary policy tools especially in the easing cycle to boost economic growth.

In the recent past, RBI has utilized various unconventional tools in addition to conventional monetary policy measures. To better understand the use of unconventional tools in the Indian economy, examples of unconventional monetary policy tools are first analysed and their applications to the Indian scenario are described. Broadly, unconventional measures can be classified into four categories—large scale asset purchases, lending operations, forward guidance and negative interest rates (BIS 2019). The key features of the measures and their applications in India are described in Table 5.

The first three of these have been applied to India and are reported in Table 4. These include Operations Twist in December 2019 and January as well as April 2020, long-term repo operation (LTRO) in February 2020, targeted long-term repo operations (TLTRO) in March and April 2020, and special refinance facilities to National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD), Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) and National Housing Bank (NHB) in April 2020.

The application of these unconventional monetary tools was necessitated, first by the slowdown in the Indian economy in 2019, and second, by the impact of COVID-19 pandemic due to which economic activity and financial markets, the world over, came under severe stress. It was thus necessary for the Reserve Bank to employ measures to mitigate the impact of COVID-19, revive growth and preserve financial stability. Thus the unconventional monetary policy tools supplemented the conventional monetary policy measures to stimulate growth in the economy.

This paper reviews the evolution of monetary policy frameworks in India since the mid-1980s. It also describes the monetary policy transmission process and its limitations in terms of lags in transmission as well as the rigidities in the process. It also highlights the importance of unconventional monetary policy measures in supplementing conventional tools especially during the easing cycle.

At the time of writing (April 2020), three and a half years have passed since the implementation of the Flexible Inflation Targeting Framework and the constitution of the Monetary Policy Committee. With the implementation of FIT, India joined the group of various developed, emerging and developing countries that have implemented inflation targeting since 1990.

The inflation target specified by the Central Government was 4% for the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation for the period from August 5, 2016 to March 31, 2021 with the upper tolerance limit of 6% and the lower tolerance bound of 2%. As shown in Fig. 11, from August 2016 through March 2020, the headline inflation generally stayed within the tolerance band with the average inflation rate slightly less than 4% during this period. There were episodes of high/unusual inflation due to supply shocks (food inflation, oil prices) but these were suitably integrated in the policy decisions.

The Monetary Policy Committee has also been in existence since October 2016. The mandate of the MPC is to set the policy repo rate while taking cognizance of the primary objective of monetary policy—to maintain price stability while keeping in mind the objective of growth—as well as the target inflation rate within the tolerance band. Once the policy repo rate is set, the monetary transmission process facilitates the percolation of the change in the policy rate to all financial markets (money and bond markets) as well as the banking sector which further impacts interest sensitive spending in the economy and eventually increases aggregate demand and output growth.

In practice, however, there are rigidities as well as lags in the transmission process that impede the speed and magnitude of the transmission and thus question the efficacy of monetary policy with respect to the policy repo rate. Nevertheless, the external benchmarking system introduced by RBI from October 1, 2019 whereby all new floating rate personal or retail loans (housing, auto etc.) and floating rate loans to micro and small enterprises extended by banks were benchmarked to an external rate, strengthened the monetary transmission process with several banks benchmarking their lending rate to the policy repo rate. This requirement of an external benchmark system was further expanded to cover new floating loans to Medium Enterprises extended by banks with effect from April 1, 2020. This is expected to further improve the transmission process.

Of course, the policy repo rate is not a panacea for all ills but serves well as a signaling rate. The RBI routinely brings out the Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies Footnote 1 that is released simultaneously with the resolution of the MPC. RBI has also taken recourse to unconventional measures to supplement the conventional tools to boost economic growth. More recently, with the slowdown in 2019 followed by the extraordinary slump in economic activity due to COVID-19 pandemic, RBI has been compelled to use rather innovative and unconventional tools starting in December 2019 as discussed in Table 5.

Needless to say, in the unprecedented times of the global pandemic (and, in general, in periods of severe crises), a multi-pronged approach comprising monetary, fiscal and other policy measures is required to protect economic activity and minimize the negative impact of the pandemic (crisis) on economic growth. The importance of monetary-fiscal coordination is highlighted in the resolution of the Monetary Policy Committee dated March 27, 2020 (available on the RBI website) that states the following: “Strong fiscal measures are critical to deal with the situation.” Thus, in addition to monetary policy, fiscal policy has a major role in combating the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. In response to the need of the hour, the Government of India has implemented various fiscal measures to provide a boost to the economy. While central banks across the globe have responded to the global pandemic with monetary and regulatory measures, various governments have reinforced the monetary measures by deploying massive fiscal measures to shield economic activity from the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A few words about the workings of the MPC are also warranted. As discussed in the paper, the voting pattern of the Indian MPC is comparable to international standards, reflecting the healthy diversity in the assessment of the members. The workings of the MPC are transparent with the resolution being made available soon after the end of the meetings. Furthermore, each member of the Committee has to submit a statement that is made available in the public domain on the 14th day after the meeting. Thus, each member is individually accountable, making the process perhaps more stringent than that of MPCs in other countries.

Statement on Developmental and Regulatory Policies sets out various developmental and regulatory policy measures and macroprudential policies for strengthening financial markets and systems, regulation and supervision, banking sector etc. from time to time.

Interest rates on fixed rate loans of tenor below 3 years shall not be less than the benchmark rate for similar tenor.

In case of newly set up banks (either domestic or foreign banks operating as branches in India) where lending operations are mainly financed by capital, the weightage for this component may be higher in proportion to the extent of capital deployed for lending. This dispensation will be available for a period of three years from the date of commencing operations.

I am grateful to Michael Patra and Janak Raj, Deputy Governor and Executive Director respectively, Reserve Bank of India for useful and constructive suggestions. I also gratefully acknowledge help and support from Hema Kapur, Deepika Goel and Neha Verma, teachers in colleges of the University of Delhi, who also motivated me to write in a student-friendly manner. Special thanks are due to Naina Prasad for competent and diligent research assistance. I am grateful to the Editors of the Indian Economic Review for inviting me to contribute to the newly instituted section on Policy Review. Earlier versions of this paper were presented as a Public Lecture at the Delhi School of Economics in March 2020 and as a Keynote Address at the Annual Conference of the Indian Econometric Society at Madurai Kamaraj University in January 2020. I am grateful to the participants of these events for their feedback.